Attachment and Grief in Addiction and Recovery

Understanding the heart and mind of person suffering from addiction

Introduction

People use drugs to get high. It is therefore reasonable to think that people who are addicted to drugs are driven by the desire to get high over and over again. However, if you ask a person coming to treatment for addiction why they continue to use drugs, they often say things like: “I use so that I can feel normal” or “I haven’t gotten pleasure from the drug in years.” If people use drugs to get high, then addiction is paradoxical—as the pleasure of drug use fades, the drive to use grows stronger and stronger. This paradox is resolved when we consider addiction not as a pleasure-seeking behavior but as a human attachment—a relationship that provides profound emotional security (however unhealthy) and that cannot be ended without significant grief.

Note: Although I began by talking about “drugs”, I use the term addiction to encompass all attachments that cause a person to radically subvert his or her own values, goals, and priorities. These attachments can include compulsive behaviors (e.g. gambling and anorexia) and unhealthy relationships (e.g. abusive or codependent relationships). If this broad classification seems odd to you, I urge you to complete this short thought experiment

before reading the rest of the article.

Understanding human attachment

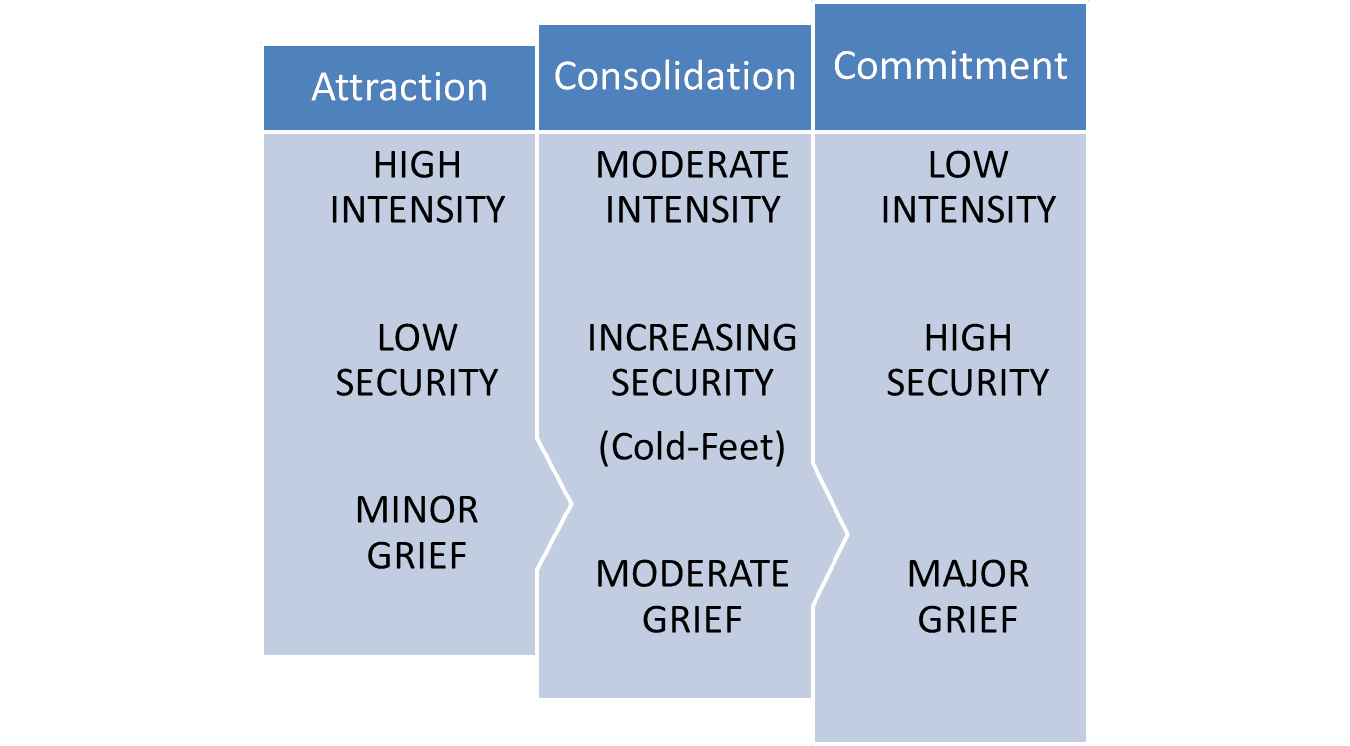

Consider the way that people fall in love. The initial romance is typically accompanied by intense excitement and pleasure. There are the first physical contacts, the exhilaration of getting to know a new person, and the first sexual encounters. When you talk to people who are falling in love, they often seem intoxicated by their new love relationship.

At some point during the initial phase of romance, reality begins to creep in. Imperfections and incompatibilities are noticed, and the romantic perspective is balanced by critical perceptions. Since these negative perceptions have largely been suppressed during the “blind love” phase of romance, they can, for a short time, become the focus of attention and usher in a period of doubting.

More often than not, the period of doubt leads to a breakup. One or both individuals realize that, despite the romance, there is not enough substance or compatibility for a committed relationship. While breaking up can be hard, the loss is usually resolved over the course of a few weeks. In general, the shorter the relationship, the shorter the process grieving.

If a couple can survive the doubting phase of the relationship, the type of reinforcement that maintains the relationship is gradually transformed. The intensity of pleasure associated with romantic love gives way to the more comforting pleasures of familiarity, security, and shared identity. Although human beings enjoy the excitement and pleasure of falling in love, they tend to opt for the less intense pleasures of a committed relationship over serial romance. Sometimes the loss of intensity can be disturbing to couples as they transition out of the romantic phase, but this change is a natural biological and psychological process. Attraction brings people together, but lasting attachment is woven with the threads of familiarity, identity, and security.

The more normal and familiar a couple’s relationship becomes, the more intensely devastating the prospect of separation. We grieve the loss of romance far more easily than we grieve the loss of attachment. While we find pleasure and excitement in romance, our attachments are our refuge in an otherwise impersonal and often frightening world.

To put it very simply, our brains attract us to possible attachments through our expectation and experience of intense pleasure. Gradually, excitement and novelty give way to familiarity and comfort. In that familiarity we find security, a security that is far more valuable to us than any romantic opportunity. The loss of an attachment is accompanied by an often debilitating process of grief.

Nor is this attachment process restricted to love relationships. Consider the prospect of choosing a profession. People generally move from interest to interest before committing to one or another profession. Any given interest is exciting at first, but when the first excitement wears off, most professions involve a lot of hard work and imperfect rewards. Some are clearly more suitable to a person’s personality than others. It is common to almost all attachment processes that there is a period of attraction, followed by a period of testing/doubting, and culminating in either break-up or commitment. Commitment entails the establishment of a new normal in which the attachment is a fixed part of a person’s life.

Addiction comes from the Latin word for “attachment” and, psychologically, it conforms to the pattern of normal human attachment. During the period of romance (e.g. recreational drug use), addictive relationships are intensely pleasurable. However, there are negative physical and emotional processes that counterbalance addictive pleasures from the very beginning—the nausea and vomiting of opioid initiation, the hangovers that follow alcohol use, the early losses experienced in gambling, and the dramatic emotional conflicts of unhealthy relationships.

As individuals become more dependent on an addictive attachment, they continue to have moments of lucidity during which they notice the negative consequences and tell themselves, “I really need to stop this behavior” or “I really need to cut back on my use.” Many people end potentially addictive attachments due to these early warning signs and negative consequences. But in persons who develop addiction, their physical and cognitive resistance is not strong enough to overcome the relief or pleasure associated with the attachment or the grief associated with its loss. Ultimately, the idea of separating from the drug, behavior, or relationship becomes more and more physically and emotionally painful even as the attachment ceases to provide much if any felt pleasure.

By the time people come to treatment for addiction, they are almost never in the romantic phase of the attachment, and their addiction maintenance has very little to do with pleasure-seeking. It is common to hear persons with addiction say: “I haven’t felt pleasure in years, but I still can’t get myself to stop.” Persons with addiction know that they are miserable and that the addiction provides only a fleeting sense of comfort, but the solution to the misery is more terrifying than the misery itself.

The emotional role of attachments

Attachment theory was developed through the study of mothers and infants, but scientists quickly realized that attachments play a crucial emotional role throughout our lives. One of the founders of attachment theory identified four key functions of all attachments. These functions can help us understand why attachments are so powerful and how they function independent of basic pleasure-seeking.

- Secure Base — Our attachments provide a familiar base from which we can deal with life’s difficulties. The caregiver’s comforting presence allows toddlers to explore their environment with confidence. Often persons with addictive attachments come to believe that they cannot engage socially or deal with normal life stress without the comforting presence of the drug. The drug becomes a secure base that makes the stress and difficulty of life seem tolerable.

- Safe Haven — When difficulties arise in our lives, we rush back to our attachments for comfort and relief. The distressed child rushes back to his or her mother’s arms. Spouses and friends call one another for support. The person addicted to drugs or alcohol, uses those drugs to relieve both normal and acute life stress.

- Proximity Maintenance — A toddler will not stray too far from his or her caregiver. The person with addiction always makes sure that the drug is accessible so that they can take refuge in it when needed. In severe addiction, the need for the drug is constant (to prevent withdrawal) so a great deal of energy is spent ensuring its availability.

- Separation Distress — When an important attachment is severed, it causes significant distress. If a caregiver dies or moves away, if a couple divorces, or if a person with addiction loses access to his or her drug of choice, the separation is accompanied by panic—the intense fear that one cannot survive without the attachment relationship.

Recovery from addiction is a complicated and lengthy grief process through which individuals gradually extricate themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally from an unhealthy attachment to drugs, alcohol, behaviors, or relationships and replace that attachment with new, healthy attachments. How long does this process take and what does it look like? It looks like any grief process—with ups and downs, negative emotions, and a strong desire to escape the new reality that has been ushered in by loss. It takes years, not months. It is often messy and painful. In those who have the internal and external resources to persevere, it culminates in a new freedom, acceptance, and appreciation of life.

Recovery as a complicated grief process

Grieving is our brain’s way of detaching from anything to which we have been strongly attached. Most people associate grief with death, but people also grieve divorce, job loss, geographic separation—any change through which a core attachment is severed. Anyone who has grieved knows that it is a horrible emotional process that can last many months or years.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross famously identified five phases of grief through which people move as they seek to integrate a difficult loss or change. It is well established in the field of grief work that people move back and forth between these stages and often experience multiple stages at once. The traditional stages of grief and their application to addiction are described below:

- Shock/Disbelief — Shock is the emotional state we experience when we are faced with a loss that we cannot comprehend. We cannot easily imagine life after the death of a loved one, the loss of a long-time job, or the diagnosis of a serious disease. All of a sudden, life as we’ve known it comes to a grinding halt. The reality of the loss is too huge to imagine or process. People who begin addiction treatment often arrive in utter disbelief that they could possibly live a life without their addictive attachment.

- Denial — Because life without an addiction is so difficult to imagine, shock often gives way to denial and bargaining. While addiction ravages their lives, people often tell themselves and those around them that they don’t really have a problem or that they can get it under control with little or no help. They minimize the consequences of their addiction and exaggerate the addiction’s positive qualities because the prospect of separating is just too difficult to face.

- Bargaining — In a sense, bargaining is just another version of denial. But instead of denying the present problem, bargaining usually involves denying the need for permanent separation from the addictive attachment. People with severe addiction comfort themselves with the idea that someday they will be able to drink or use or return to the abusive lover. Another typical form of bargaining is replacement. It’s common to hear someone say: “I had a problem with heroin but I’ve never had an alcohol problem. It’s okay for me to drink.” Replacement short-circuits the grieving process and can become as detrimental as the original addiction.

- Anger — When people successfully separate from their addictive drug, behavior, or relationship, they face a world that is now empty of the thing that gave them the greatest sense of familiarity, comfort, and security. With the loss of that secure base, life feels empty and dissatisfying. The natural human response to such a bad situation is to fight against it and struggle to change it. Anger fuels that fight. Unfortunately, that anger can easily become focused on the very things that are aiding recovery. People feel anger towards their family members, their treatment providers, their mutual support groups, their monitoring and accountability structures—everything that is helping them to maintain separation from drug use. Even clients that are cooperating with the process of separation find themselves inwardly raging against everything that is supporting their sobriety. Often in early recovery, I tell clients that I know their relapse prevention plan is an effective one when they’re angry about it. That anger shows me that they have truly structured their lives so as to prevent a return to their addictive attachment.

- Depression — Depression is what people feel when they've given up the fight and perceive themselves as helpless to find any meaning or purpose in their lives. They are facing a world without their addiction and their appraisal of that world is—IT SUCKS! Life seems to have less meaning, purpose, and enjoyment when an addictive attachment has been severed. A negative view of life naturally causes depression. In recovery, depression can easily lead to relapse when a person begins to withdraw from all the relationships and activities that are supporting recovery. Alone again in isolation, it is all too easy to turn back to the only relationship in which they remember feeling good.

- Acceptance — Acceptance happens gradually. It begins when an individual finds him or herself beginning to enjoy things again—having moments of positive appreciation of life without the addictive attachment. Gradually, this new life comes to feel normal and the motivational system becomes oriented toward non-addictive activities and relationships. Acceptance is not a moment of realization or a decision—it is a gradual process in which one good hour in a day becomes two good hours, and one good day in a week becomes two good days. Eventually, over many months, it happens that there are more good hours than bad hours and more good days than bad days. At that point, life begins to feel more normal, more enjoyable, and more sustainable without addiction.

I cannot stress strongly enough how irrational the phases of denial, bargaining, anger, and depression can be or how long into addiction treatment they can last. It is typical to speak with individuals who are more than a year sober but are still bargaining with future possibilities to use or return to their addiction. Some begin to imagine that their recovery is itself proof that they were originally misdiagnosed and should now be able to have a healthy relationship with their addiction. The battered woman, the heroin addict, and the alcoholic all utter the same mantra as they head toward relapse: “It will be different this time.” This belief develops in utter denial of all the harm that their addiction has caused and all the clear evidence that they are physically, emotionally, and psychologically incapable of transforming their addictive relationship with a drug, behavior, or person into a normal healthy relationship.

Complicated Grief

The persistence of these cognitive distortions is troubling, but it is not difficult to understand from a grief perspective. Consider these three scenarios:

- Alex goes off to war and is “Missing in Action” but never declared dead. His wife Claire remains at home. She knows that soldiers have died without being identified and that many other soldiers have been taken alive by the enemy. Years pass, and Claire struggles to know whether she should continue wait or try to move on. Finally her family convinces her to accept Alex’s death. She sets herself to the task of grieving and finds that she simply can’t believe that he is gone when there is a shred of hope that he is still alive

- Eric is in a five year long relationship to a woman named Maggie whom he plans to marry. They live together and, although the relationship has its problems, the couple often speaks of having children and imagines the type of life they want to share. Suddenly, Maggie ends the relationship, telling Eric that although she loves him, she doesn't want to spend her life with him. Reluctantly, Eric moves into an apartment a few blocks from her. He continues to call and stop by, and engages in long conversations with her about repairing their relationship. Despite Maggie’s clear communication that the relationship is over and the consistent advice Eric receives to move on, Eric cannot let go. More than a year after their breakup, Eric sees Maggie on the sidewalk kissing another man and smiling with excitement. Eric’s heart plunges. The next month he takes a job in another state, stops contacting Maggie, and begins the hard work of moving on.

- Michael is a professional marathoner at the height of his career when he suddenly collapses during a training run. Luckily he is rushed to the hospital by a passing car and resuscitated. By the following day, he feels fine and is released from the hospital. During the next two weeks, Michael undergoes a battery of testing. He is ultimately diagnosed with a genetic heart valve defect that the doctor says will prevent him from continuing his running career. The defect is one that gets worse with strenuous activity and eventually leads to death. With an implanted defibrillator and a non-aerobic lifestyle, Michael will have a normal life expectancy, but a regimen of strenuous activity will very likely kill him in just a few years. When hearing this diagnosis, Michael storms out of the doctor’s office in disbelief. Just that morning he had gone for a 12 mile run and felt great. At home, he calls a physician friend to arrange for a second opinion.

Each of these stories is one of complicated grief. Grief can be complicated by a number of factors, but one factor is especially brutal—i.e. the perception that the loss might yet be avoidable. The real process of letting go starts when a person gives up denial and bargaining and accepts the basic fact of the loss. When a glimmer of possibility remains, it is extremely difficult to move past the stages of denial and bargaining and to allow oneself to feel the awful emotions that accompany permanent loss.

In the first example, Claire is powerless to re-unite with her husband but can’t let go of the possibility that he will return. In the second example, Eric refuses to believe that his relationship with Maggie is over because he still perceives some possibility that their relationship can be repaired. It’s only Maggie’s new relationship that makes the breakup real to him. In the third example, Michael the marathoner is in denial about his diagnosis. If the second opinion is similar to the first, the prospect of dying young will force him to take the matter seriously and grieve the loss of running career. This grief process will likely entail an inner struggle between what he knows and how he feels. He’s been running for years and feels great—what’s the harm of one more run?.

The difficulty of accepting loss when the possibility of avoiding it remains real is not a moral defect. It is the way our brains are wired. When we partner with someone over several years or develop a successful career, we come to experience these attachments as core components of our survival and security. Our brains do not relinquish this type of relationship easily. From a simple cost-benefit perspective, it is more economical to spend a few years working to prevent the loss of an important attachment than to start from scratch.

It is easy from the outside to see that addictive attachments are unhealthy. Rather than facilitating security and survival, they cause pain, insecurity, and destruction. They are nevertheless coded in the brain through the same neural pathways that form our healthy human attachments. The process of detachment from addiction is complicated most of all by the fact that accessibility to drugs, behaviors, and relationships can be moderated but never completely removed. Alcohol is in every grocery store, heroin in every city, and codependent or abusive lovers are usually ready to take their old partners back. In a matter of seconds, reunion with an addictive attachment will remove grief and restore an (albeit fleeting) sense of comfort and security.

Successfully achieving and maintaining separation from an addictive attachment is a complex and difficult task. The next essay in this series will aim to demystify the recovery process by 1) identifying the core components of relapse prevention and 2) explaining how and why these components can be used to achieve long-term recovery.